The Value of Being Outdoors

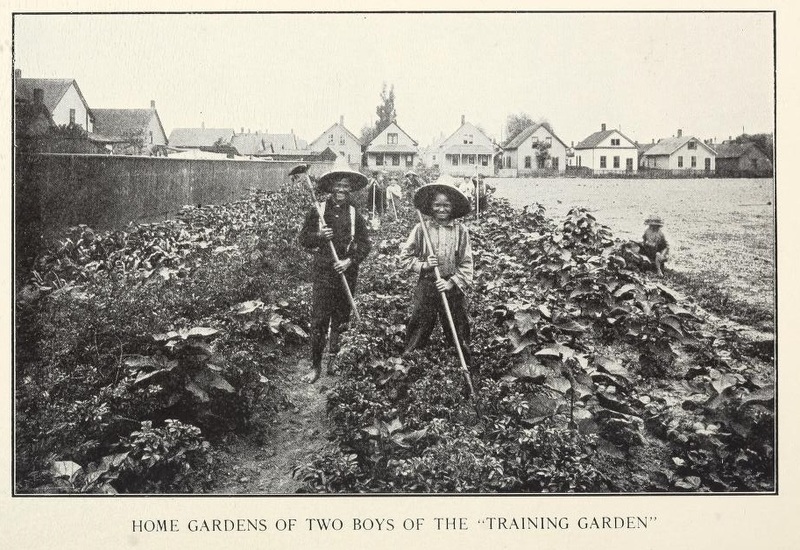

The ability of garden work to require children to spend time outdoors was also seen as valuable:

"The activities of school garden work are natural to the child and give much needed respite from school-room restraint....The child's mind gets growth out of them because it can understand them. Not only does the school garden serve to educate and train, but it supplies a kind of knowledge that is highly useful and cultivates a taste for an honorable and remunerative vocation."

Spillman, W.J. Agrostologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture (1903). Significance of the School Garden Movement, First Report of the American Park and Outdoor Art Association, Program of the Seventh Annual Meeting. Buffalo, NY , p. 49. Quoted in Greene, Maria Louise. Among School Gardens, pp. 36-37

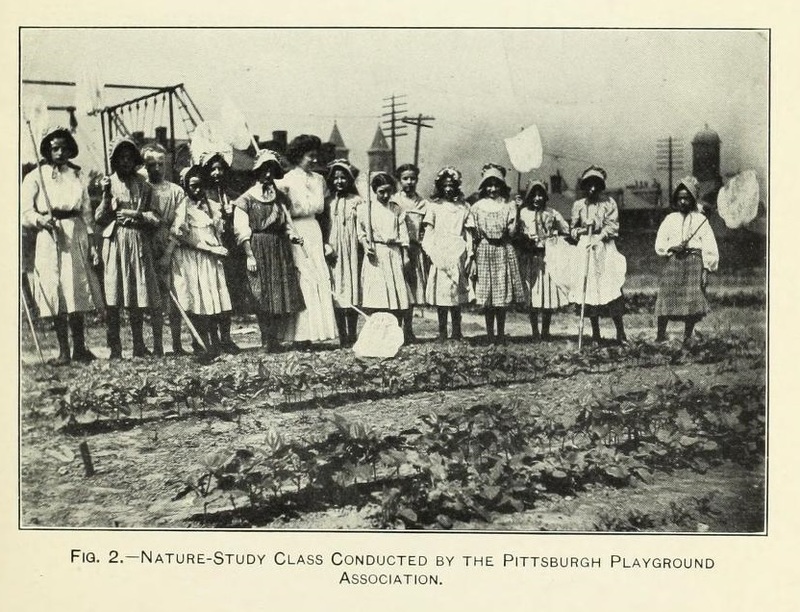

In 1906, Lucy R. Latter pointed out both the value of outdoor activity conducted in concert with nature and the danger of too much indoor confinement:

"In dealing with the effect of gardening upon the children, we must keep in view their threefold nature, and remember that, although the physical, the intellectual, and the moral sides exist throughout, one side is more predominant than the others at a given time in the development of the human being. In the earliest years the physical nature is more to the fore. Gardening is an outdoor occupation. The child is, therefore, continually in the fresh air, and one has only to watch him when engaged in the work to see how thoroughly he enjoys it. His whole heart and soul are involuntarily thrown into it, and no task seems too much for him, so does 'the labour we delight in physic pain.'

The child's labour in the garden involves a variety of movements, and affords a natural outlet for much of that physical energy which, if left unprovided for, leads to rough play and unruly practices, and, later, even to hooliganism itself."

Latter, Lucy R. (1906). School Gardening for Little Children. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Company, Limited, pp. 153-154

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.