Hookworms

An unidentified illness

In the late 1800s, medical scientists noticed that a general condition of poor health had become widespread in parts of the southern United States. A recognizable pattern of symptoms emerged. Anemia, impaired learning, stunted growth, and digestive disorders resulted in chronic weakness and long-term disability among people in the South.

An unidentified illness, scientists believed, was lowering productivity and causing people to remain mired in poverty at a time when other agricultural areas of the country were experiencing economic growth. They began to suspect the problem was hookworm. Hookworm disease was known in Europe, but very few cases of European hookworm had been documented in the United States. Prior to the early 1900s, people with symptoms similar to hookworm disease were often misdiagnosed with unrelated conditions, such as malaria or dropsy. A common set of symptoms pointed to hookworm infection, and attention shifted toward finding out whether this disease was responsible for the pervasive sickness in the South.

New species of hookworm discovered

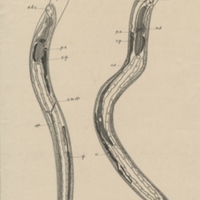

In 1901, zoologist Charles Wardell Stiles of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Animal Industry began studying the problem. His investigations led him to the discovery of a new species of hookworm, Necator americanus (Uncinaria americana), which differed from its European counterpart. The American hookworm was found to be common in the southern U.S. and in Latin America. Stiles traveled throughout the southern Atlantic states in 1902, conducting examinations and mapping the geographic distribution of the disease.

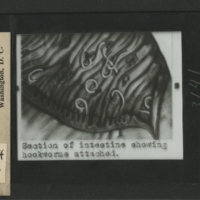

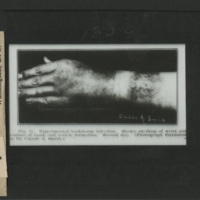

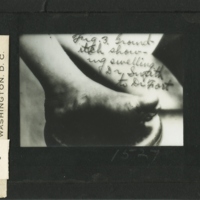

The hookworm parasite is common in warmer climates. Its larvae live in the soil. Typically, the larvae enter humans by burrowing into their skin, often through the soles of the feet. Once inside the body, the larvae are carried by the blood stream into the lungs, throat, and then into the digestive system. They reach adulthood in the human intestine. The worms attach themselves to the intestinal wall and feed on nutrients from their host’s blood. Adult worms lay eggs inside a person’s body, which are passed out of the digestive system in the stool. The eggs contaminate soil they come into contact with, and the life cycle begins again.

Stiles found that hookworm disease occurred most commonly in rural areas. It thrived where the soil was sandy, but not in areas with clay soil. He described hookworm disease (known by the scientific name uncinariasis) as “one of the most important and most common diseases of this part of the South, especially on farms and plantations in sandy districts” (Stiles, 1902a). He concluded that a lack of basic sanitation, along with poor nutrition, contributed to southerners’ susceptibility to hookworm infection.

Illustrations below are by L.H. Wilder for "The Sanitary Privy,"

Public Health Report No. 17, by Charles Wardell Stiles (1910)

Rockefeller Sanitary Commission

Shortly after his discovery of American hookworm, Stiles transferred to the U.S. Public Health Service (predecessor of the National Institutes of Health). He helped organize a campaign, funded by John D. Rockefeller, Sr., to rid the South of hookworm disease. The Rockefeller Sanitary Commission for the Eradication of Hookworm Disease (RSC) surveyed hookworm infection rates among children, and indeed they were high—over 40 percent of children were found to be infected.

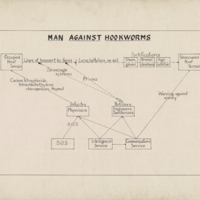

The RSC implemented a strategy to combat the disease. It sent healthcare workers and mobile dispensaries to provide free deworming medication to people in affected areas. At the same time, the commission launched an information campaign to teach doctors and members of the public how to recognize symptoms of hookworm disease and how to prevent the disease by improving sanitation. By the time the commission ceased its hookworm program in 1914, the rate of this disease in the South had been dramatically reduced.

Resources:

“Rockefeller Sanitary Commission (RSC).” 2015. 100 Years: The Rockefeller Foundation. Accessed May 22, 2015. http://rockefeller100.org/exhibits/show/health/rockefeller-sanitary-commissio.

Stiles, Charles Wardell. 1902a. “Hook-Worm Disease in the South--Frequency of Infection by the Parasite (Uncinaria americana) in Rural Districts.” Public Health Reports 17 (43): 2433–34.

———. 1902b. “A New Species of Hookworm (Uncinaria americana) Parasitic in Man.” American Medicine 3 (19): 777–78.

———. 1903. Report upon the Prevalence and Geographic Distribution of Hookworm Disease (Uncinariasis or Anchylostomiasis) in the United States. Hygienic Laboratory Bulletin 10. Washington, DC: U.S. Public Health and Marine Hospital Service. https://archive.org/details/reportuponpreval00stilrich.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.