Swine Sanitation

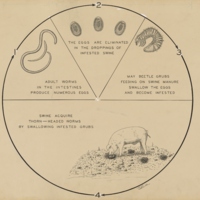

Prior to the 1920s, farmers raised swine on permanent pastures or lots where generations of hogs had been kept before them. Over time, the soils in these pastures accumulated waste from many animals, some of which were carriers of intestinal parasites. Worm eggs that passed into the soil with hog droppings were picked up by the next season’s piglets, and parasite infections flourished.

Parasitic diseases made raising swine a difficult and financially risky enterprise. Stunted growth due to parasite infections meant farmers had to feed pigs longer before they were market-ready, adding to the cost of raising them. Not only did producers face the problem of poor returns for unfit stock, but some animals did not survive to reach the market. It was not uncommon for such losses to drive farmers out of hog production altogether.

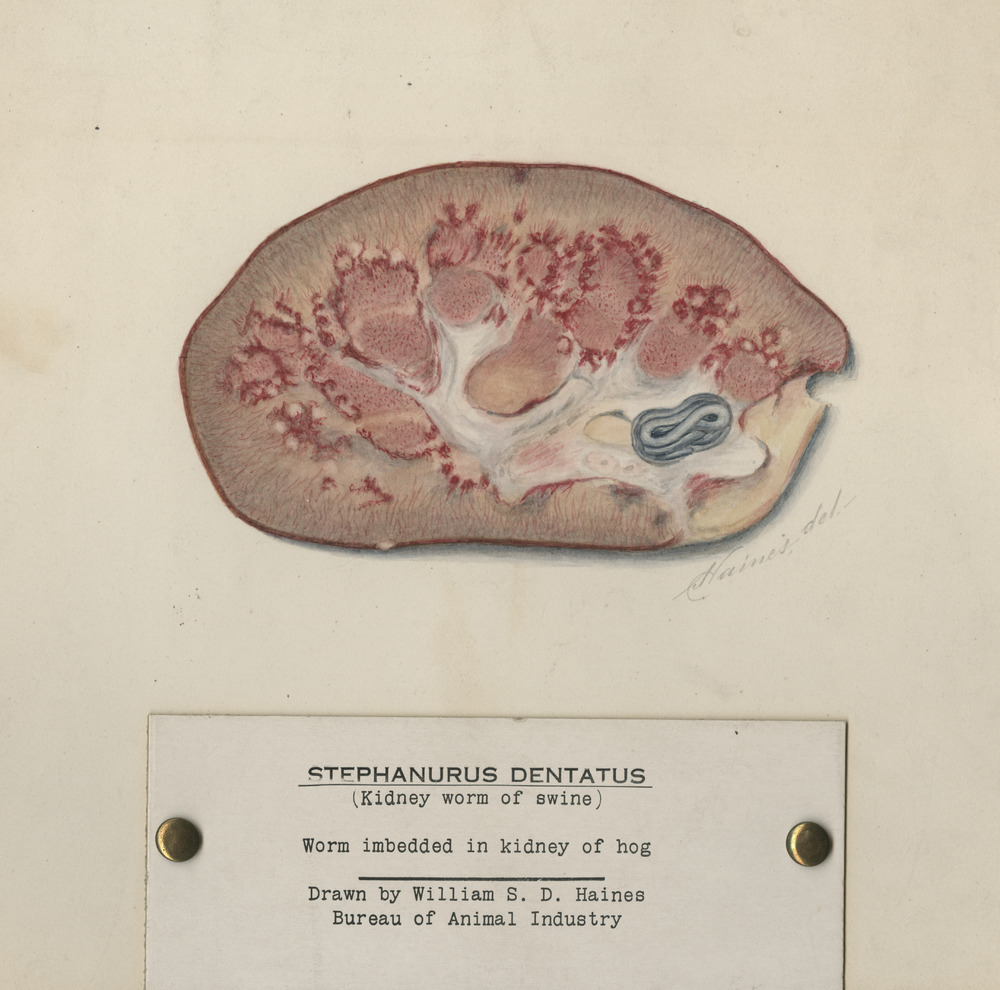

“In the general run of hogs in certain sections of the south 85 to 90 percent of livers go to the tank and the loins quite commonly penetrated by the parasite, thus destroying portions of the choicest parts of the hog.” “The Possibilities for Swine Production in the South,” undated

McLean County System of Swine Sanitation

In 1919, Brayton H. Ransom and Hayes B. Raffensperger of the Bureau of Animal Industry’s Zoological Division collaborated with farmers and the McLean County (Illinois) Farm Bureau to develop sanitary measures for controlling internal parasite infections in young pigs. Their research led to a system for raising hogs free from the destructive intestinal roundworm Ascaris suum.

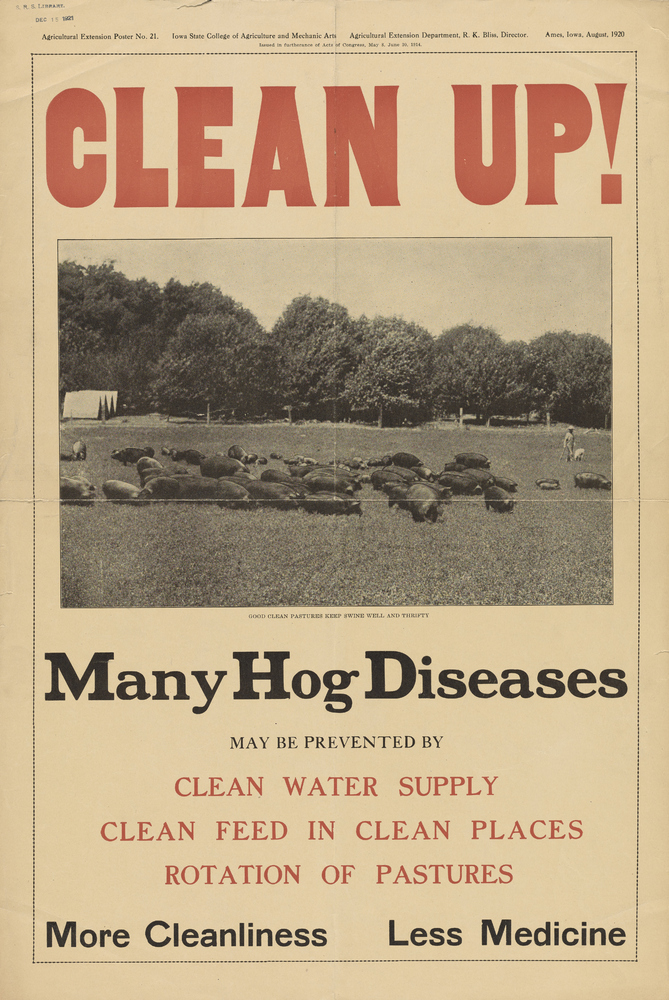

The McLean County System of Swine Sanitation, named for the place where it was developed and tested, was the first systematic method for controlling Ascaris suum infection in pig litters. The McLean system controlled not only worm infections, which were responsible for substantial losses to the swine industry, but it prevented other filth-borne diseases as well.

The McLean County System of Swine Sanitation was designed to prevent parasites from infecting new pig litters. The system consisted of four steps:

- Cleaning and disinfecting farrowing pens prior to each farrowing season (spring and fall).

- Washing sows before they were put in clean farrowing pens.

- Moving sows and their pigs to clean pastures, i.e., where no hogs had been kept for at least a year. Best practice included making sure the field had been cultivated since it was last used for raising hogs in order to eliminate prior contamination.

- Keeping pigs confined to clean pasture until they were at least four months old and more resistant to infections.

Reports showed that using the McLean system’s sanitary practices resulted in improved pork production. Pigs raised this way generally grew faster and were more uniform in size than pigs raised under traditional practices. More pigs could be raised from fewer sows because losses decreased. Young pigs reached market weight several weeks earlier than pigs raised with old methods, which meant lower feed costs and better economic gains for farmers.

Baltimore and Ohio railway car " Swine Sanitation Special", undated. H. B. Raffensperger, Zoological Division, traveled on this demonstration train in Ohio where he and others examined more than half a carload of pigs that were brought in for post-mortem. In every case, they found from 3-7 different species of parasites.

Swine Sanitation Work at Moultrie, Georgia

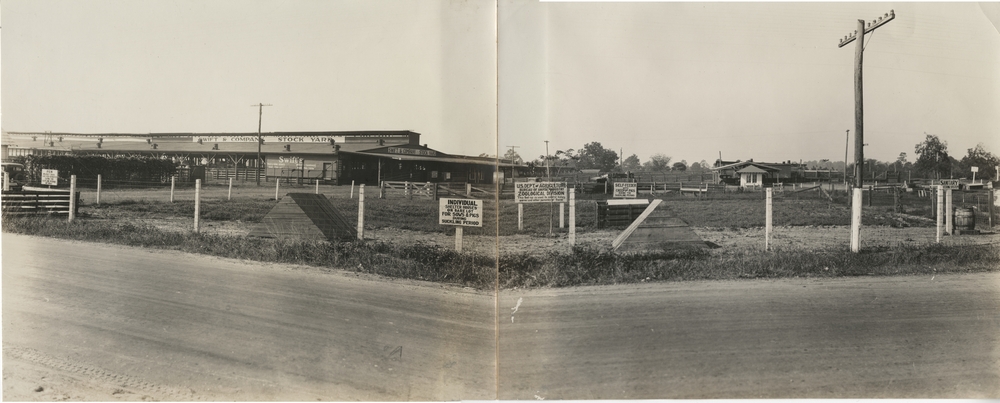

Parasite-related swine losses also plagued Georgia’s coastal plain region, where pork production was becoming an increasingly important industry by the mid-1920s. The USDA’s Bureau of Animal Industry teamed up with a commercial pork processor, Swift and Company, to build a research facility on company-owned land in Moultrie, Georgia in 1926. Specialists in veterinary medicine and parasitology from the BAI began investigating methods for controlling swine parasites endemic to the southeastern United States. Local farmers and vocational students served as cooperators and conducted experimental work.

Having achieved successful results with the McLean County swine sanitation system, USDA parasitologists adapted the system to Georgia’s climate and soil conditions. By 1934, the modified southern system was in place. The USDA spread the word and instructed farmers in how to apply swine sanitation methods through demonstrations at many community locations and events, including: the Moultrie, Georgia research facility (and Tifton, Georgia after 1941), fairs, exhibitions, local organizations such as the Future Farmers of America, vocational education cooperative programs, veterinary conferences, and short courses in agriculture.

Farmers of the South can now grow hogs practically free from internal parasites and can save thousands of dollars’ worth of meat for food purposes, such as livers, kidneys, leaf lard, and loins, if they will follow the methods worked out by the U.S.D.A. at Moultrie, [Georgia]….T. G. Walters, Teacher of Vocational Agriculture, Moultrie, Georgia, undated

Resources:

“Accomplishments of Helminthological Investigations.” n.d. U.S. National Animal Parasite Collection Records. Box 98, Folder 3. Special Collections, National Agricultural Library.

Andrews, John S. 1993. Animal Parasite Research in the Zoological Division, Bureau of Animal Industry, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C., 1923-1938. Beltsville, MD: Animal Parasitology Institute, BARC-East, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

“Conceptual Firsts Accomplished in Helminthological Investigations.” 1961. U.S. National Animal Parasite Collection Records. Box 98, Folder 3. Special Collections, National Agricultural Library.

Raffensperger, H. B. n.d. “Parasites of Swine (Treatment and control).” U.S. National Animal Parasite Collection Records. Box 98, Folder 3. Special Collections, National Agricultural Library.

Robbins, E. T. 1926. Cheaper and More Profitable Pork through Swine Sanitation: A Review of the McLean County System of Swine Sanitation on Illinois Farms during 1925. Circular 306. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois.

Schwartz, Benjamin. 1934. Controlling Kidney Worms in Swine in the Southern States. U.S. Department of Agriculture Leaflet 108. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. https://archive.org/details/controllingkidne108schw.

“The Possibilities for Swine Production in the South.” n.d. U.S. National Animal Parasite Collection Records, Box 136, Folder 1. Special Collections, National Agricultural Library.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. 1924. Annual Reports of the Department of Agriculture for the Year Ended June 30, 1923. Report of the Secretary of Agriculture. Reports of Chiefs. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Walters, T. G. n.d. “Turn Your Feeds into Pork, Not Worms.” U.S. National Animal Parasite Collection Records. Box 136, Folder 10. Special Collections, National Agricultural Library.

Wilson, M. C. 1926. Swine Sanitation : Excerpts from 1925 Annual Reports of State and County Extension Agents. Extension Service Circular 22. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture. https://archive.org/details/swinesanitatione22wils.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.