1951-1953

Sanibel, Florida: The First Test Site

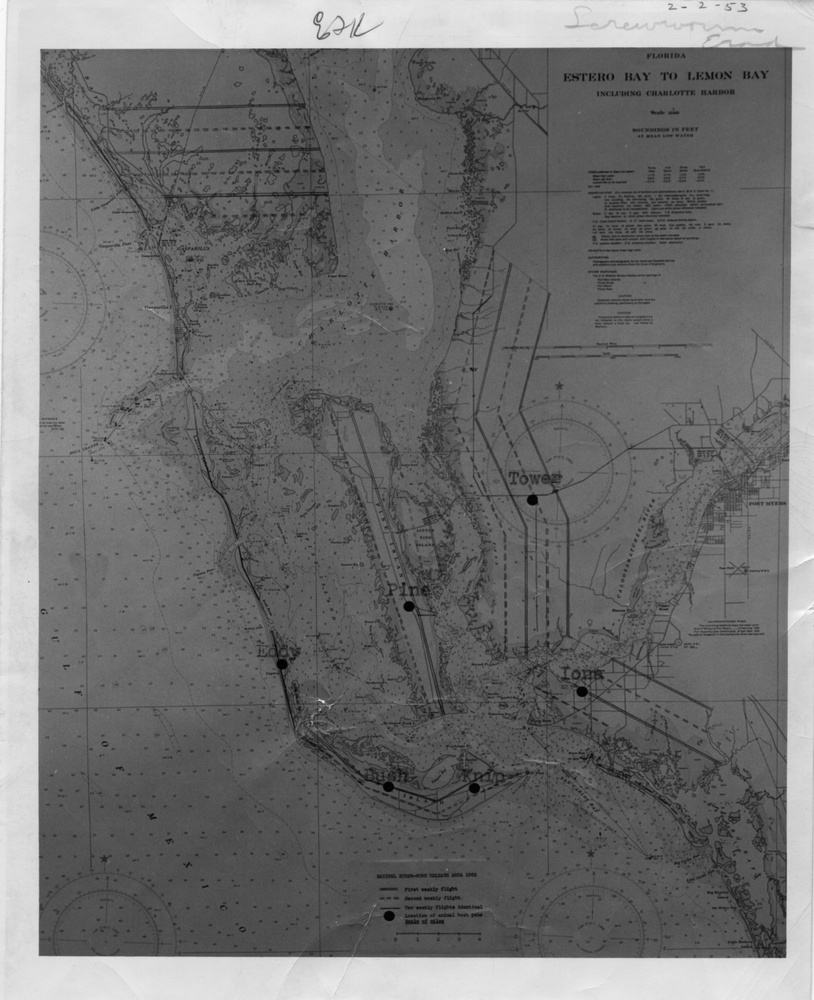

In the fall of 1951, an eradication field test was set up on Sanibel Island, an island 4 miles off the west coast of Florida. Sanibel Island's small size made it a good place to test whether wild screwworm populations could be overwhelmed by large numbers of laboratory-reared sterile flies.

Goats Used to Track Screwworm Population

The research plan was to artificially wound goats in order to track the screwworm population on a controlled basis. Scientists set goat pens around the island so they could monitor the goats' health and check infested wounds. Carefully placed fly traps provided data enabling calculation of the ratio of sterile to fertile flies. These ratios helped determine the progress of the program and the level of eradication on Sanibel Island.

Sterile Flies Released

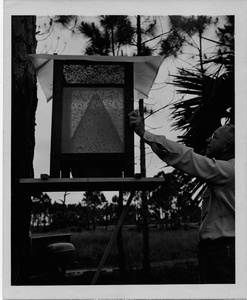

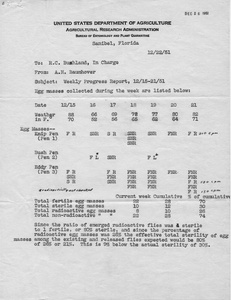

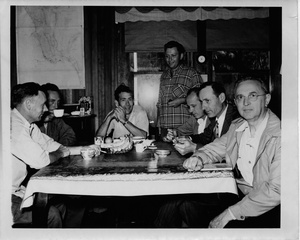

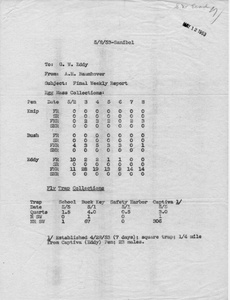

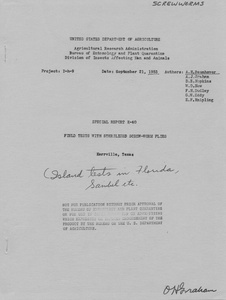

The Kerrville, Texas, laboratory, under the direction of Raymond C. Bushland, reared and sterilized the flies released on Sanibel Island in 1951. For every fertile fly released, 10 sterile flies were released; scientists marked released flies with small amounts of radioactive material for tracking purposes. Researchers collected egg masses off the goats to determine if they were from screwworms and gathered screwworm flies from the traps to see if they were sterile. Alfred H. Baumhover, the lead Agricultural Research Service (ARS) entomologist, A.J. Graham, and A.L. Smith made daily recordings of screwworm activity and wrote weekly progress reports to Bushland and Knipling.

Fly-Rearing Facility Erected in Orlando, Florida

The initial 1951 tests showed that the screwworm population was diminishing, making it possible to continue the experiments during 1952 and 1953. Construction of a fly-production and research laboratory in Orlando, Florida, made the transportation of laboratory-reared flies and communication more efficient. Scientists in Orlando marked their flies with phosphorus and placed them in small paper cups. Pilots dropped the flies from a specially modified plane that had a chute which extended beneath the wing to disperse the cups.

Sanibel: An Impetus for Further Screwworm Research

The field test staff reluctantly ended the Sanibel experiments in the spring of 1953. The island was not completely free of screwworms, but the scientists were cautiously optimistic about the future of the technique. Screwworm infestations reappeared on Sanibel Island due to its proximity to the mainland, which was well within the flies' flight range. Yet the Sanibel Island program provided evidence that the Sterile Insect Technique was sound. Sanibel's results became an impetus for further research.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.