____________

Crop Development

Field Work, Tuskegee

(between ca. 1910 and ca. 1915). Bain News Service, Publisher. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Late in [Carver’s] life, he recalled the shock he experienced on his first trip to Alabama, in October, 1896: ‘When my train left the golden wheat fields and the tall green corn of Iowa for the acres of cotton, nothing but cotton, my heart sank a little….The scraggly cotton grew close up to the cabin doors; a few lonesome collards, the only sign of vegetables; stunted cattle, boney mules; fields and hill sides cracked and scarred with gullies and deep ruts…not much evidence of scientific farming anywhere. Everything looked hungry: the land, the cotton, the cattle, and the people.’ Indeed, historian Mark Hersey has pointed out that even a half-century before Carver arrived at Tuskegee, ‘the country’s single greatest agricultural problem was erosion, and cotton cultivation was the single biggest contributor to it.’

One of the first things Carver did during his early tenure at Tuskegee was to undertake a series of experiments through which he tried to understand what plants would grow well in the Alabama soil and which ones would help to build up the soil and provide good forage. Understanding that black Macon County farmers did not have money for expensive seeds and fertilizers, he attempted to focus on techniques that would cost farmers little more than their own hard labor and ingenuity.

Kremer, G.R. (2011). George Washington Carver: A Biography. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, pp. 79-80.

Carver published the results of his studies on the value of growing and developing various (non-cotton) crops such sweet potatoes, cowpeas, small grains, corn, alfalfa, and plums in several Experiment Station Bulletins. (He also acknowledged the primacy of cotton for poor black Alabama farmers in two publications.) Carver backed up his observation of Alabama upon his arrival, "Everything looked hungry: the land, the cotton, the cattle, and the people" by exorting his audience to expand its products beyond cotton to crops that would better fill their stomachs and wallets. This effort to develop and expand the range of crops for these farmers is the central subject for the Bulletins in this section.

View Exhibit

Farm Management

Mathematics Class at Tuskegee Institute

(1906). Johnston, Frances Benjamin, 1864-1952, photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. LC-DIG-ds-03647

‘Now, in the first place as farmers, we should not be ashamed of our occupation. We all know well that people in general have come to think of the farmer as man with a great crowned hat…; with huge rough boots all covered with dust or mud; with trousers course and untidy and well stained with soil, and with manners awkward, uncouth and ludicrous, and he himself of very limited intelligence. And we all too wrong[ly] are wont to assent to this idea of the farmer and foolishly show ourselves abashed when we come into the presence of men who represent the profession. But we should put away this mistaken notion, brace ourselves up and show to all that we esteem our occupation an honorable one. We should learn too that it is all erroneous and false to say or think that it requires little or no intelligence to be a farmer. Indeed, on the contrary, it requires the highest intelligence and the highest type of intelligence to be a farmer. For he who would be a farmer must deal with, must understand and must acquire the mastery over all the puzzling forces of nature.’

"Prof. Geo. W. Carver visits Homer College--a farmers' conference organized." (July 2, 1908). The Christian Index, Jackson, TN. Quoted in Duncan, P. (2005). George Washington Carver: For His Time and Ours. George Washington Carver National Monument. National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, p. 38. Retrieved from: https://www.nps.gov/gwca/learn/management/upload/GWC-For-His-Time-Ours-Spec-History-Study.pdf

Carver's central focus was always on improving the lives of the poor black farmers in the area surrounding Tuskegee, Alabama specifically and in the Southern United States, generally. The three Experiment Station Bulletins featured in this section of the exhibit take up the practical tasks required for successful farm management and the skills necessary to complete those tasks. Other historic publications that address overall farm management issues and marketing specific crops are also featured.

View Exhibit

Homemaking Activities

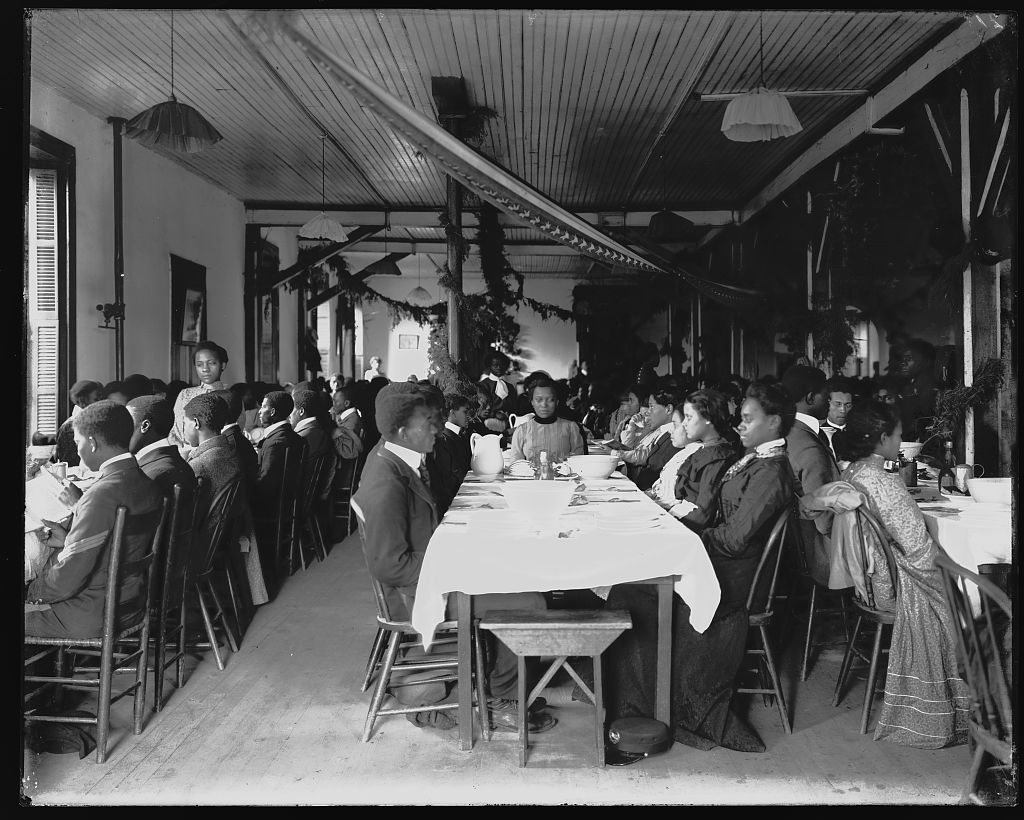

Interior View of Dining Hall, Decorated for the Holidays, With Students Sitting at Tables at the Tuskegee Institute

(circa, 1902). Johnston, Frances Benjamin, 1864-1952, photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. LC-J694-21 [P&P].

'What Carver comes to see,' [Mark] Hersey says, was that 'altering [black sharecroppers’] interactions with the natural world could undermine the very pillars of Jim Crow.' Hersey argues that black Southerners viewed their lives under Jim Crow through an environmental lens. 'If we want to understand their day to day lives, it’s not separate drinking fountains, it’s ‘How do I make a living on this soil, under these circumstances, where I’m not protected by the institutions that are supposed to protect its citizens?' Carver encouraged farmers to look to the land for what they needed, rather than going into debt buying fertilizer (and paint, and soap, and other necessities—and food). Instead of buying the fertilizer that 'scientific agriculture' told them to buy, farmers should compost. In lieu of buying paint, they should make it themselves from clay and soybeans.

Kaufman, R. (February 21, 2019) "In Search of George Washington Carver’s True Legacy." Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/search-george-washington-carvers-true-legacy-180971538/

Carver saw his mission as part of a larger program to empower poor black farmers in every aspect of their lives. Thus, the subject matter of the Experiment Station Bulletins addressed typical agricultural areas of concern, but also the domestic aspects of farm life such as food preservation, cooking, growing ornamental plants, and using native clay to create color washes for decorating the farmhouse. These homemaking activities are the areas of focus for the Bulletins in this section.

View Exhibit

Raising Livestock

Poultry Raising in Macon County, Alabama

George Washington Carver. (1912). Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute Experiment Station. Bulletin Number 23.

At a typical conference, held in 1899 at Hampton College in Virginia, Carver acknowledged the bleak financial situation facing black farmers in the South, noting that the ‘average southern farm has little more to offer than about thirty-seven percent of a cotton crop selling at four and a half cents a pound and costing five and six to produce.’ However, he added that ‘we have a perfect foundation for an ideal country [including] natural advantages of which we may justly feel proud.’ What was holding poor farmers back, he contended, was their ignorance of ecological relationships, or as he put it, the ‘mutual relationship of the animal, mineral and vegetable kingdoms, and how utterly impossible it is for one to exist in a highly organized state without the other.’ Thus, the problems, as he saw it, was a lack of agricultural education (and a failure on the farmers’ part to apply those things they had already learned through events such as the one at which he was speaking.) Of course, he did offer ‘practical’ suggestions, most of which (in this particular case) had to do with increasing, ‘both in quantity and quality, all of our farm animals.’ ‘We should…sacrifice,’ he suggested, ‘a goodly number of the worthless puppies that are in evidence in too many dooryards, and put two or three sheep in their places.’

Hersey, M. (2006). "Hints and suggestions to farmers: George Washington Carver and rural conservation in the South." Environmental History, 11(2), p. 248. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3986231.

Carver offered practical suggestions for the best, most economical ways to raise livestock, including poultry, hogs, and cattle in several Experiment Station Bulletins. His specific focus was on the sources of feed and methods farmers should use to nourish their animals. This effort to develop and expand the range of agricultural production for the black farmers of the south to animals is the central subject for the Experiment Station Bulletins in this section.

View Exhibit

Rural Schools

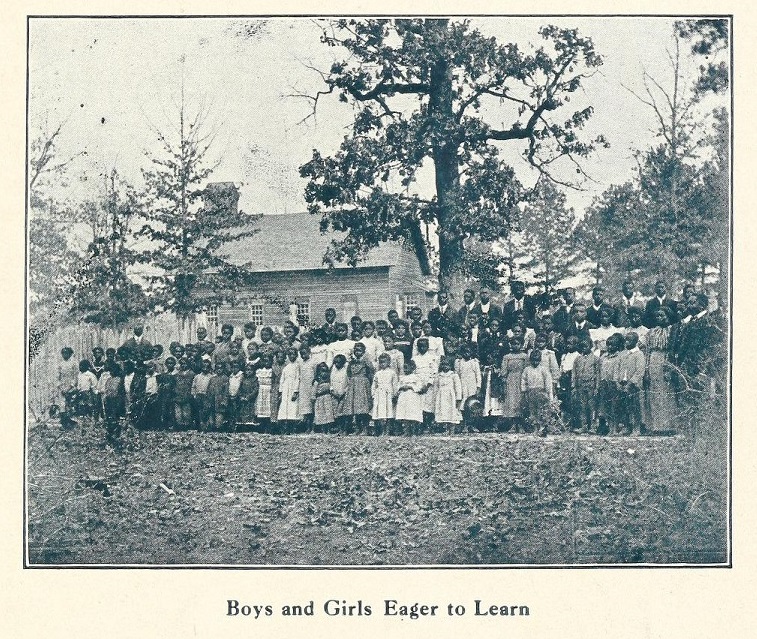

Boys and Girls Eager to Learn from Cover of Nature Study and Gardening for Rural Schools

(1910). George Washington Carver. Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute Experiement Station. Bulletin Number 18.

Carver’s innovative teaching methods and enthusiasm for his subjects proved inspirational to his [Tuskegee] students. Many, for example, took him up on his challenge to collect and identify various specimens. This sort of hands-on learning was related to the trend popular throughout the country at the turn of the century, though especially applied to rural, elementary school-age children, of integrating ‘Nature Study’ into the formal education of students. At the request of Liberty Hyde Baily, a Cornell horticulturalist and leader in that movement and in the wider agricultural reform efforts of the early twentieth century, Carver served on the editorial board of the national journal, The Nature-Study Review. Not surprisingly, Carver published bulletins from Tuskegee voted to Nature Study and issued ‘Farmers’ Leaflets’ from the institute’s aptly named ‘Bureau of Nature Study for Schools and Hints and Suggestions to Farmers.’ His pedagogy so impressed Booker T. Washington that Tuskegee’s president asked him to lead seminars for his fellow faculty members on how they might improve their teaching.

Hersey, M. (2006). "Hints and suggestions to farmers: George Washington Carver and rural conservation in the south." Environmental History, 11(2), pp. 245-246. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3986231.

Carver created two Experiment Station Bulletins targeting rural schoolchildren specifically. This section of the exhibit features these two publications, along with a sample of educational works addressing issues of agricultural concerns published in the same time frame.

View Exhibit

Soil Productivity

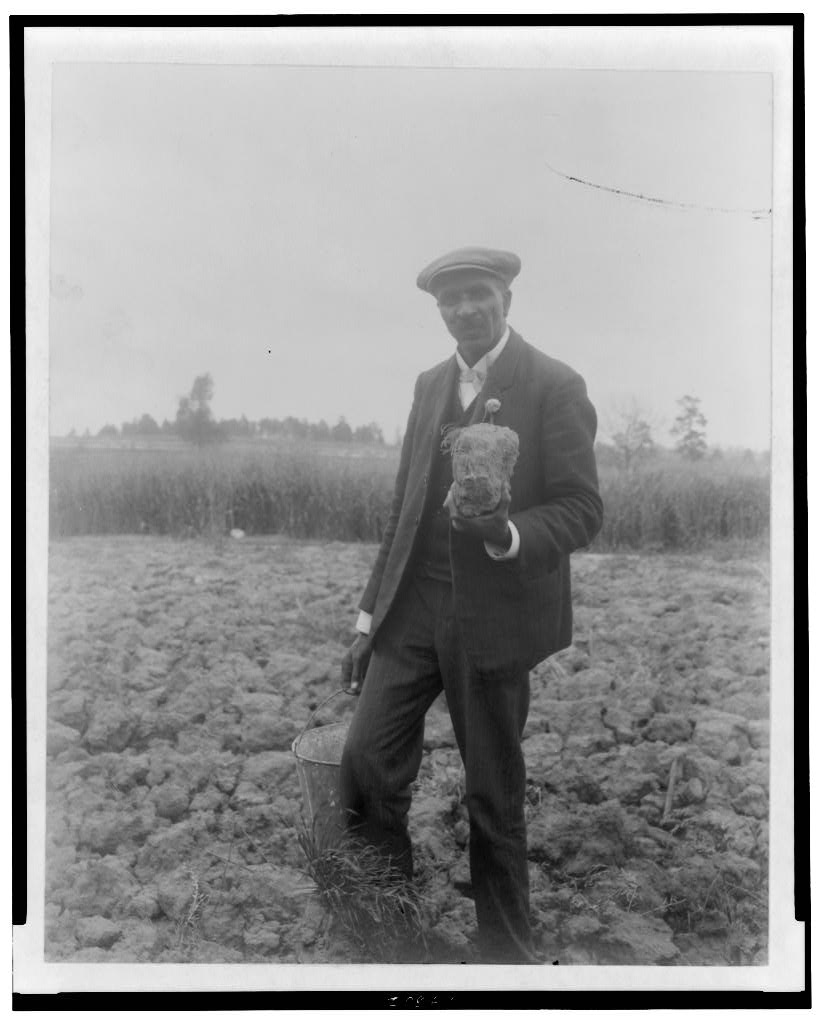

George Washington Carver, Full-Length Portrait, Standing in Field, Probably at Tuskegee, Holding Piece of Soil

(1906). Johnston, Frances Benjamin, 1864-1952, photographer. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. LC-USZ62-114302

The heart of Carver’s message to Southern farmers was that the type of farming they had been practicing had drained their soil, vampire-like, of its vitality, and that the soil’s fertility could be restored. The Montgomery Advertiser published this statement of his in 1938: ‘Whenever the soil is rich the people flourish, physically and economically. Wherever the soil is wasted the people are wasted. A poor soil produces only a poor people—poor economically, poor spiritually and intellectually, poor physically.’

Burchard, Peter Duncan (2005). George Washington Carver: For His Time and Ours.

National Park Service. Department of the Interior, p. 18. Retrieved from: http://www.nps.gov/applications/parks/gwca/ppdocuments/Special%20History%20Study.pdf.

Carver published the results of his studies on soil productivity in four Experiment Station Bulletins. Like all of his other scientific work, Carver's soil studies were done in an effort to develop practical methods that could be put to work by the smallest farmer with very little inital investment in materials and tools. The soil science publications of Carver's Station form the focus of this section of the exhibit, along with a small sample of U.S. Department of Agriculture publications on the same topic.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.