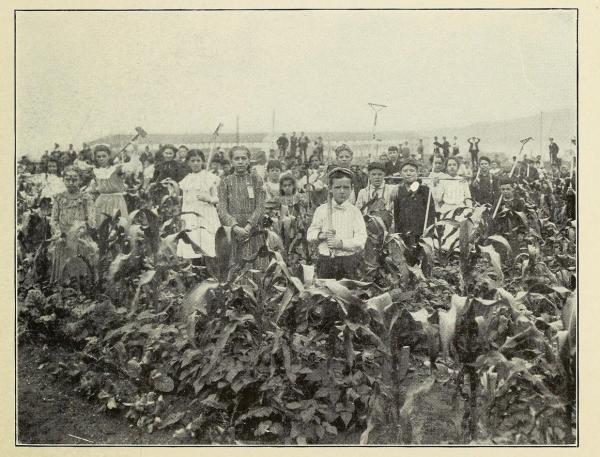

Sipe, Susan Bender (1912) Some Types of Children's Garden Work. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Office of Experiment Stations Bulletin, Number 252, Plate I

Gardening is essentially practical. There is nothing better fitted for the healthful development of children. It affords opportunity for spontaneous activity in the open air, and possibilities for acquiring a fund of interesting and related information; it engenders habits of thrift and economy; develops individual responsibility, and respect for the rights of others; requires regularity, punctuality, and constancy of purpose.

Miller, Louise Klein (1904). Children's Gardens for School and Home: A Manual of Cooperative Gardening. New York: D. Appleton and Company, p. 5

In 1906 the U.S. Department of Agriculture estimated that there were 75,000 school gardens in the United States (Jewell, 1907, pp. 37-38). The first American school garden was established in 1891 at the George Putnam School in Roxbury, Massachusetts. The peak of the school garden movement was reached in the years immediately following World War I when War Gardens turned into Victory Gardens and the urgency for surplus food production began to wane. The value and use of school gardens is enjoying new life however, with the popularity of the local food movement, USDA's current Farm-to-School Program, and the USDA's People's Garden.

This review of the school garden movement in the early 1900s reveals the roots of school gardening as an educational tool designed to enrich many aspects of children's lives.

School Garden: Definition

Advocates of school gardens differed on the amount of attention they placed on various program elements such as studying the scientific life of the plant, producing food, marketing food products, engaging with the natural world, being outdoors, or taking responsibility for a specific plot of land. Mary Louise Greene offered a succinct definition that touched on several of these essential elements:

A school garden may be defined as any garden where children are taught to care for flowers, for vegetables, or both, by one who can, while teaching the life history of the plants, and of their friends and enemies, instil [sic] in the children a love for outdoor work and such knowledge of natural forces and their laws as shall develop character and efficiency.

Greene, Mary Louise (1910). Among School Gardens. New York: Charities Publication Committee, p. 3.

Individual or Group Plots

Some practitioners felt that each school garden should be a product of the individual effort of a single child:

The idea of ownership and the rights of ownership, which come from the possession of a garden, induce the pupil to exercise his ability to make his possession as good or better than that of his neighbor. The natural result of this is industry. Business experience is an important result of harvesting and accounting for the products which are grown. The right of ownership and a respect for property rights are more largely developed from the possession of individual gardens than in community gardens. The idea that 'what's mine is my own' becomes very strongly developed, with the natural sequence that such possessions must be properly protected and all rights concerned respected. On the other hand, a party interest in a community garden does not so emphatically develop the idea of individual responsibility, and each one has a tendency to care less for the plants which another has shared in producing, with the result that responsibility is shirked, and there is lack of interest, with a consequent lack of industry. For this reason, in our work from the very inception the individual garden idea has been emphasized and strictly adhered to.

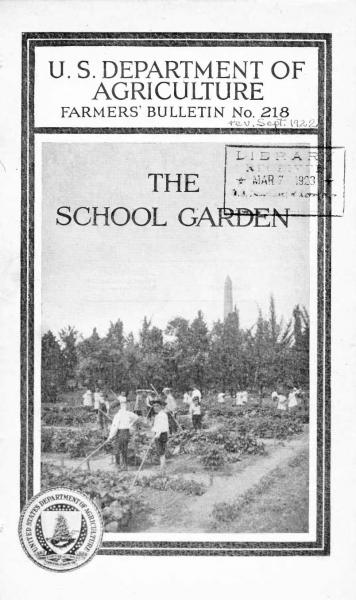

Corbett, L.C. (1922) The School Garden). U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers' Bulletin, Number 218, p. 4

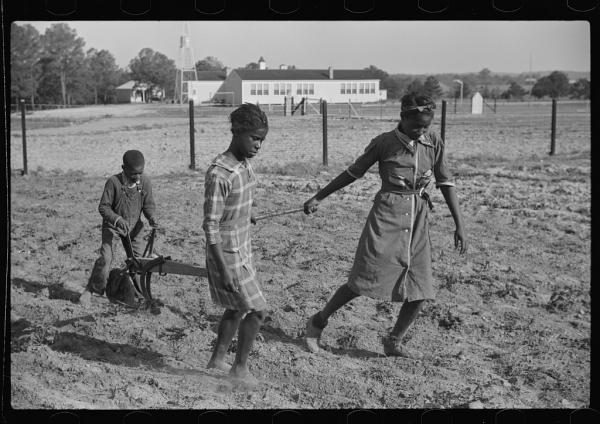

Wolcott, Marion Post, photographer (1939) Working in School Garden, Gees Bend, Alabama. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-fsa-8a40108. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.

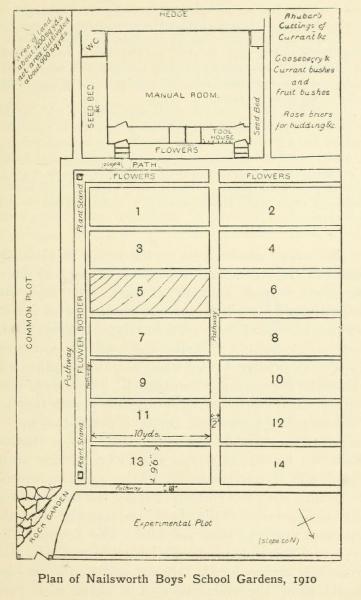

G.W.S. Brewer illustrated a garden plan including 14 separate plots that could be used by either a single child or a team of 2 students:

Plan of Nailsworth boys school garden, 1910. Brewer, G.W.S. (1913). Educational School Gardening and Handwork. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 11

In School Gardening for Little Children Lucy R. Latter advocated the value of group work for small children:

Here I would like to say that experience amply proves that outdoor gardening with little children should only be taken as group work — that is to say, with but a small number of children at a time. Except for such work as watering the beds, or removing any stones from the same, when more children may easily be employed, from eight to ten children are about as many as one teacher alone can keep really occupied at a time, for she has to superintend and direct so many different operations the while. One bed may require weeding, another may have to be raked over, whilst in the kitchen garden there may be some runnerbeans to string up, or some carrots to thin out, and numberless other things.

Latter, Lucy R. (1906). School Gardening for Little Children. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Company, Limited, pp. 15-16

Hine, Lewis Wickes, photographer (1917) School garden - Jefferson School. Location: Muskogee, Oklahoma. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-nclc-00686. National Child Labor Committee Collection.

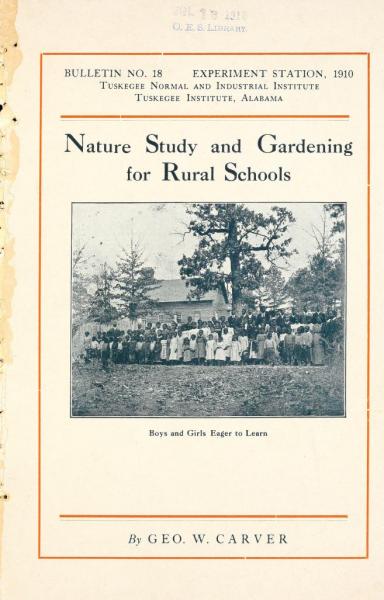

George Washington Carver contended that school gardens should be managed as partnerships among students, created and managed through written contracts:

It has been the experience of many teachers that it works well to have two, three or four children form a partnership, under written contract, who will be assigned by the teacher to one of the little plots set apart as an individual garden. The contact is made very simple, written somewhat as follows: Contract We agree to 1. Raise vegetables on one of the plots set apart for us to garden 2. Follow as best we can the direction of our teacher. 3. Share equally in the expense, labor and profits of the garden.

Carver, George Washington (1910) Nature Study and Gardening for Rural Schools. The Tuskegee Agricultural Experiment Station Bulletin Number 18, p. 6.

Others maintained that the nature of the garden as individual or the product of the collective effort of an entire class or school was immaterial to its value as an educational tool:

From the point of view of this book the school garden is any garden in which a boy or girl of school age takes an active interest....The gardens to be considered from this point of view may be collective or individual, or both; they maybe in-doors or out-doors, or both; they may be at the school or the home, or both. In all of these cases the plants to be grown are much the same and the methods involved in growing them are similar.

Weed, Clarence Moores and Emerson, Philip (1909) The School Garden Book. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 3

Urban and Rural Gardens

Many publications pointed out the differences in nature and purpose between urban and rural school gardens:

It is obvious that no set rules can be laid down for the management of a school garden. In the heart of a city the work may be an entirely different thing from what it is in a rural or semirural district. In the city the main idea may be an aesthetic one combined with moral and physical training. The general trend of the work in this country is practical, so that its application will eventually have more or less effect on our industrial development. Manual training has been made a feature in many of our schools, and no one will deny that valuable results have been obtained from it.

Galloway, B. T. (1905) School Gardens: A Report Upon Some Cooperative Work with the Normal Schools of Washington, With Notes on School-Garden Methods Followed in Other American Cities. Office of Experiment Stations, Bulletin Number 160, p. 7

Brewer, G.W.S. (1913) Educational School Gardening and Handwork. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

In School and Home Gardening: A Text-Book for Young People, Kary Cadmus Davis pointed out some of the benefits of gardening for the child in the country:

The effect of the garden in the country is to fill the mind of the child with thoughts which are elevating and not degrading. Idle hands and leisure hours are as bad for the country children as for others. The wholesome refinement of the garden fills the place of vulgar twaddle. Country children learn to love their future life occupation. They find it has a scientific foundation.

Davis, Kary Cadmus (1918) School and Home Gardening: A Text-Book for Young People. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, p. 4

L.C. Corbett contended that gardens in country schools should be very different from those in city schools because rural children were already intimately familiar with basic agricultural elements and processes:

As a rule, children in rural districts are familiar with the fundamental operations of the garden — preparation of the soil, planting the seed, and the cultivation and harvesting of the ordinary garden and farm crops. To attempt, therefore, to maintain the ordinary type of individual vegetable and flower garden upon the grounds of rural schools would undoubtedly be an unwise expenditure of time and energy....

The plan of procedure, therefore, for teachers in rural districts, should be quite different from that followed by those in urban communities. The teachers of the rural schools will find a most fruitful field along the line of laboratory experiments, which will demonstrate the principles of plant growth and of plant nutrition, methods of propagation, etc....

In rural communities, instead of conducting miniature vegetable or flower gardens, it might be better to secure different varieties of grains or grasses for test upon home plats, encouraging the students to undertake small experiments which shall have for their chief end the development of the faculties of observation. Different methods of tillage and fundamental principles of this character will be involved in these experimental or demonstration areas, the results of which will emphasize the importance of certain lines of work.

Corbett, L.C. (1922) The School Garden. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Farmers' Bulletin, Number 218, p. 5

Wolcott, Marion Post, photographer (1939) Behind the Homemade Plow in the School Garden, Gees Bend, Alabama. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-fsa-8a40110. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.

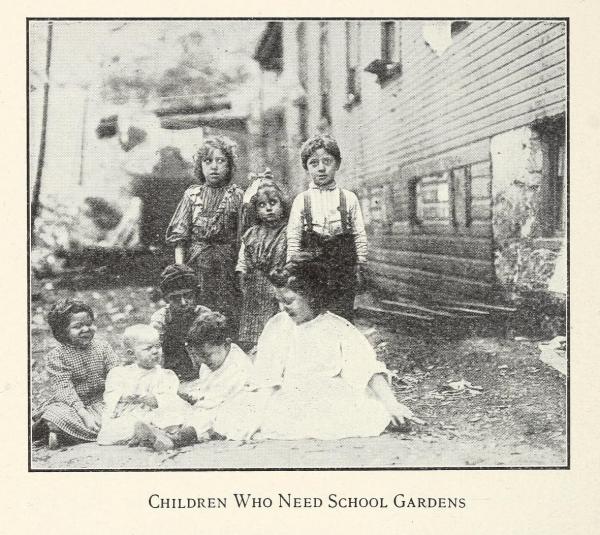

A school garden at Dewitt Clinton Park in the heart of New York City. Miller, Louise Klein (1904). Children's Gardens for School and Home: A Manual of Cooperative Gardening. New York, D. Appleton and Company, p. 38

Greene made the case for the teaching of gardening to city children:

Perhaps best of all is that the teaching of the saner and sweeter side of life which comes when the school garden takes the child off the city streets, away from crowded alleys, vicious surroundings...when it finds happy work for idle hands, health for enfeebled bodies, and training for the will and affections.

Greene, Maria Louise (1910) Among School Gardens). New York: Charities Publication Committee, p. 36

The Value of Being Outdoors

The ability of garden work to require children to spend time outdoors was also seen as valuable:

The activities of school garden work are natural to the child and give much needed respite from school-room restraint....The child's mind gets growth out of them because it can understand them. Not only does the school garden serve to educate and train, but it supplies a kind of knowledge that is highly useful and cultivates a taste for an honorable and remunerative vocation.

Spillman, W.J. Agrostologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture (1903). "Significance of the School Garden Movement," First Report of the American Park and Outdoor Art Association, Program of the Seventh Annual Meeting. Buffalo, NY , p. 49. Quoted in Greene, Maria Louise. Among School Gardens, pp. 36-37

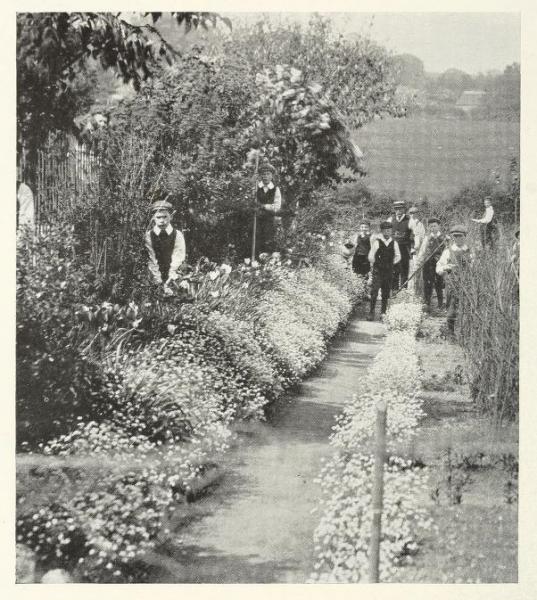

Greene, Maria Louise (1910) Among School Gardens. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, Plate 17

In 1906, Lucy R. Latter pointed out both the value of outdoor activity conducted in concert with nature and the danger of too much indoor confinement:

In dealing with the effect of gardening upon the children, we must keep in view their threefold nature, and remember that, although the physical, the intellectual, and the moral sides exist throughout, one side is more predominant than the others at a given time in the development of the human being. In the earliest years the physical nature is more to the fore. Gardening is an outdoor occupation. The child is, therefore, continually in the fresh air, and one has only to watch him when engaged in the work to see how thoroughly he enjoys it. His whole heart and soul are involuntarily thrown into it, and no task seems too much for him, so does 'the labour we delight in physic pain.'

The child's labour in the garden involves a variety of movements, and affords a natural outlet for much of that physical energy which, if left unprovided for, leads to rough play and unruly practices, and, later, even to hooliganism itself.

School Gardening for Little Children. (1906). London: Swan Sonnenschein & Company, Limited, pp. 153-154

Cooperative gardening is one of the newer movements for the education of the young and for the elevation of neglected and unfortunate classes ; yet it has already become an important factor in the school and home life of many places under the auspices of school authorities, civic leagues, improvement associations, women’s clubs, settlement houses, libraries and other bodies.

This movement has two motives — the transforming of barren, dreary, ill-kept school grounds and other uncared-for public places into bowers of beauty and good taste, and developing in children love of Nature, appreciation of her beauties and ability to enhance for their own enjoyment and the public good the esthetic effect of their immediate surroundings.

The child at play in make-believe and game, at work in garden, is thus a true technodramatist, from whom would-be educators, be they scientific or technical, have much to learn before they can adequately teach.

But life and education are more than industry, and even art? Assuredly; but so also is a child's garden. Here in this modest little volume are also indications enough of how each teacher, in her own way — not necessarily yours nor mine — may express to her charges her poetic associations, her aspirations, and ideals.

Here, then, from the kindergartens, so long repressed and despised, and still by many so grudgingly tolerated, there are arising examples and influences towards the needed transformation, alike of the material environment and of the inward functioning of our schools, at all levels. Nay, pointing and leading directly towards the needed transformation of our whole modern city development ; for it will be for this coming generation of child-gardeners themselves to make the Garden City.

The chief mission of this little booklet is that of emphasizing the following points:

1. The awakening of a greater interest in practical nature lessons in the public schools of our section.

The thoughtful educator realizes that a very large part of the child’s education must be gotten outside of the four walls designated as class room. He also understands that the most effective and lasting education is the one that makes the pupil handle, discuss and familiarize himself with the real things about him, of which the majority are surprisingly ignorant.

2. To bring before our young people in an attractive way a few of the cardinal principles of agriculture, with which nature study is synonymous.

If properly taught the practical Nature study method cannot fail to both entertain and instruct.

'Among School Gardens' is intended, (1) To answer the questions: What are school gardens? What purpose do they serve? Where are the best? (2) To give such explicit directions that a novice may be able to start a school garden; and to show that even the simplest one can be of great benefit to children. (3) To share with those already interested in school gardens knowledge of work done in different places.

Greene, Maria Louise (1910). Among School Gardens. New York: Charities Publication Committee

School garden work has become so general within the past five years and literature relative to the same so abundant that facts of the nature furnished in earlier reports would be superfluous, viz, what to plant, the distances apart of the rows and of the seeds in the row, and like detailed information. Teachers need now to view the garden from a higher plane — its relation to daily living, its effect upon character development, its place in the curriculum, and its relation to other subjects in the course of study. Therefore, in making this report such facts have taken a more prominent place than the ones that may be obtained from textbooks.

The individual plat system and the young gardener, owner of all he raises, is the system in vogue east of the Rockies. West of the Rockies almost invariably the commercial side holds a place of importance equal with the cultivation, but the products are sold for the benefit of the school. Children are taught business methods through the sale. The system of teaching agriculture used is always based on the best local practice and is one that children can follow intelligently, but the products are always the property of the school.

School gardening is not necessarily gardening, any more than cardboard work in school is box-making; or woodwork carpentering. Gardening should be a school subject, taken as far as possible on the lines of other school subjects, notably woodwork. The latest principles of teaching woodwork applied to school gardening would help to lift this subject into its fit and proper place. It is in itself a most interesting subject and of utilitarian value. So far, the latter idea has been the chief aim and object of the teaching. In some quarters, however, the subject has been made unduly to correlate with the work of all classes and in all sorts of subjects simply for the sake of showing correlation. While it is important to realise how much of the school work can be interwoven with the garden work, the subject must not be taught for the sake of correlation. Such an aim would be extreme, and should be deprecated. Often, too, less is thought of the educational value of the subject to the children, than of what the man in the street' will say, if perchance he look over the garden wall and see a line out of the straight, a boy holding a tool wrongly, a few weeds growing on a plot, or the least thing amiss.

Those who are charged with the direct presentation of school garden work to children will recognize that the point of view for city children must be different from that for country children. As a rule, children in rural districts are familiar with the fundamental operations of the garden — preparation of the soil, planting the seed, and the cultivation and harvesting of the ordinary garden and farm crops. To attempt, therefore, to maintain the ordinary type of individual vegetable and flower garden upon the grounds of rural schools would undoubtedly be an unwise expenditure of time and energy.

For city children, however, to whom the growth of the plant is like the discovery of a new world, the application of the simple operations involved in the maintenance of the individual garden containing flowers and vegetables is altogether a different matter. The plan of procedure, therefore, for teachers in rural districts, should be quite different from that followed by those in urban communities. The teachers of the rural schools will find a most fruitful field along the line of laboratory experiments, which will demonstrate the principles of plant growth and of plant nutrition, methods of propagation, etc. In this connection we have therefore outlined two classes of work which will encroach more or less upon each other, but the discriminating teacher will have no difficulty in selecting that which is best suited to the conditions by which he or she is surrounded.

In rural communities, instead of conducting miniature vegetable or flower gardens, it might be better to secure different varieties of grains or grasses for test upon home plats, encouraging the students to undertake small experiments which shall have for their chief end the development of the faculties of observation. Different methods of tillage and fundamental principles of this character will be involved in these experimental or demonstration areas, the results of which will emphasize the importance of certain lines of work.

An official website of the United States government.

An official website of the United States government.